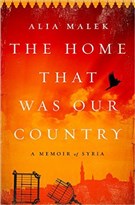

With those who would kill him waiting at each of the gates of Damascus should he try to escape, Saul of Tarsus, the man who would come to be known as Christianity’s St. Paul, fled nonetheless. Crouching in a basket, he was lowered over the city’s walls by his supporters, and he fled into the Syrian night.

It was nearly two thousand years ago that Saul, a soldier, came from Jerusalem to Damascus, dispatched and hell-bent on a mission to arrest followers of Jesus Christ—a man who, among other things, had led an affront to the ruling regime of Rome and the Jewish clergy. But instead, along the road to Damascus, his journey was interrupted by what Christian lore describes as the appearance of Jesus (post-crucifixion) in a light so strong that Saul was blinded.

Crippled, his men had to lead him into the city. He took refuge in a house on the Street Called Straight. For days, he refused food or water. His eyes were useless, covered in scales, until a Damascene disciple of Jesus miraculously restored his sight. Saul was re-born as Paul. He now joined those he had been sent to persecute.

Immediately after his defection, he began preaching of his conversion to the Syrian people. Having betrayed those whose cause he had previously served, they soon came for him.

It was a pursuit rooted in a belief—which appears to persist today—that keeping Damascus secure from revolutionary ideas was merely a matter of getting rid of the people that held such thoughts in the first place.

I wonder if those who feared what Paul was preaching breathed a sigh of relief once he was gone—did they think that now they could keep what was brewing under control?

***

Bashar al-Assad surely has heard of Paul.

If he does not know that Paul, and the movement he joined, Christianity, which went on to change Syria and the world, then he surely has passed the marked spot in the still-standing wall where the saint made his famous escape. It is in the heart of Damascus, a celebrated part of Damascus.

The parable of Paul seems tailor-made (made in Syria, after all), and had Bashar heeded its lesson—that an idea can outlast human mortality—it might have saved him some killing, and saved thousands of Syrians from dying.

But then, perhaps he has been too inculcated in his family’s cult, which has spent the last forty years forcing the notion that Syria—her wealth and her destiny—belongs to them and them alone. To them, it is as if Syria herself would cease to exist if they were not here to bridle her and rule her.

The omnipresent billboards, posters, murals, mosaics, and statues of Bashar’s dead father (the progenitor), himself (the accidental heir), and his dead brother (the assumed heir)—or what Syrians wryly refer to as “the Father the Son and the Holy Ghost”—vulgarly assert that this ancient place was only born when they forced their way to power.

Maybe it is only natural that Bashar thinks that stopping the tide of history requires simply re-writing it through lies and omissions, or reshaping it into an impossible choice between him and an intolerant sectarianism that he himself enabled. To Bashar, defeating ideas and ideals is simply a matter of silencing the voices speaking them, and disappearing them into the infamous prison at Tadmor, a town adrift in the remote Syrian desert.

That with the man or the woman goes the revolution.

That the sand makes them mute and the rest of us deaf.

***

Tourists used to flock to that same desert, drawn to Tadmor’s other offering—the Hellenic and Roman ruins of Palmyra, which were abandoned once more, once the world stopped coming here last year.

The prison, notorious for its horrible conditions, torture, and summary executions, had also been abandoned in 2001. Bashar al-Assad closed it shortly after coming to power, in what many hoped was an indication that things might change under his rule—one sleekly branded as young, modern, and reform-bound.

He reopened the prison in June 2011 in the wake of the anti-regime protests.

On the remaining grand columns of Palmyra there are still legible inscriptions to the empire’s last leader, the fate of whom Syria herself would warningly whisper in Bashar’s ear.

Her name was Zenobia. She lived and ruled in the third century, when Syria was a part of the Roman Empire, the superpower in the region and the world. But Zenobia had ambitions of creating her own independent empire. For a time, she was tolerated by Rome, which was busy with other conflicts and interventions, until circumstances abroad changed, and she eventually became much more of a liability than an asset. Thus, in 274, the Roman Emperor Aurelian sacked her city of Palmyra. Zenobia retreated, making a last stand in Emesa—the modern day Syrian city of Homs, where earlier this year the Assad regime gambled that its own fates would rise and those of the revolution would fall.

But Zenobia could not win in Emesa and was captured, taken alive by Aurelian’s forces.

History quotes her as saying, in true regional fashion, “I am a queen; and as long as I live, I will reign.”

The Romans, however, forced her from power and from Syria, taking her back to Rome. There, she was paraded through its streets, bound in chains of gold.

I am thinking of her, thinking of how she could not see that it was time to fold. I want to tell her (or him?) that yes, even if they are all just playing a part, the play can outlast your part.

I am thinking of baskets and golden chains, of defections and UN lassos.

***

At the Syrian National Museum in Damascus, placards in the exhibit on the Palmyra (or Tadmor) Basin say that evidence of “More than a million years of human occupation” has been unearthed there. The text goes on to describe how “More than simply a succession of cultures, analysis reveals a succession of ruptures or breaks.”

Indeed. Perhaps it has something to do with the fact there is no history of rulers leaving here of their own accord, even before today, before the modern Syrian republic itself was born in 1946. From the Romans to the Persians to the Umayyads to the Ottomans to the French and everyone in between, empires have been forced along only to be replaced by other, dramatically different empires, each time with Syrians making the requisite official alterations. The faces or inscriptions on the currency would be changed, religions would be converted, taxes would be paid to a new capital, a strange language would become lingua franca, another flag would be raised, and everything that came before would officially be forgotten.

Similarly, Syria’s modern history has been one of coups, countercoups, and exiles, with governments changing almost as frequently as the years. Apparently, Syria just does not do transitions, carryovers, or power-sharing. This cycle of ruptures and breaks, which often dictates amnesia as official memory, has enabled serious avoidance tendencies. (I have always had a suspicion that a survey of these million years of human occupation would reveal in Syria a disproportionately high number of disowned family members, excommunicated faithful, self-exiled or émigrés, and people practicing to ridiculous lengths the principle “he or she is dead to me.”)

As a nation-state, it has meant never having to deal with and, in fact, avoiding the difficulties of negotiating through different visions to reach a point of co-existence where all citizens can realize their fullest potential, and the resulting state can flourish. Thus, the response to the very normal growing pains of creating a dynamic nation-state here has been to simply and absurdly amputate the aching limbs. Hafez al-Assad refined this tactic, seeing any attempts by the society to grow, evolve, and express itself outside of his control as unforgivable affronts to be broken and then broken some more.

He came to power in 1970 in the final coup and rupture that brought Syria to a grinding halt and brings us to where we are today, with over forty years of one-family rule.

In 1980, however, it was a rupture in my grandmother’s brain that brought our family to a standstill, transforming her into a shell of who she had once been and who she could have yet become.

***

She was from Hama—a city best known outside of Syria these days primarily for massacres of dissenters. Inside Syria, it is also known for large churning watermills along the Asi River, fine woven fabrics, fields of wheat, and its tough-as-nails people.

Shortly after the new republic was born, my grandmother left Hama and moved to Damascus as a new bride. She never hid that she was less than enamored with her husband—he being twelve years her senior—who though intellectual and kind, would never be the debonair womanizer she had fallen in love with but was forbidden to marry.

Her marriage was but one in a series of frustrations rooted in her bad luck to have been born female. Her six brothers married as they pleased, even when their father similarly disapproved of their chosen brides for being too poor, too foreign, or too modern. Perhaps what she envied the most was that her father lavished her brothers with university educations and training—even in Europe and America. She always knew she would never receive more than a high school diploma. Once she understood the head starts her father gave the boys would not be hers, she sought to make her own fortunes. Marriage to a man from Homs and living in Damascus was her way out of Hama.

Throughout her life, she exhibited the entrepreneurial Syrian spirit that of late has better flourished outside of Syria and enriched other countries. After years of The Father stifling it, and then years of Junior stealing it, skimming the profits of other people’s good ideas by forcing them to sell majority stakes to his family. In her day, my grandmother invested small amounts of money in different businesses, bringing the agricultural yields from the farms near Hama to the people in the capital. Slowly, she bought and sold property, easily supplementing her husband’s salary.

In her house in Damascus, she played host to the spectrum of people that make up Syria: farmers, generals, artists, bureaucrats, housewives, fortune-tellers; Kurds and Armenians; Villagers and urbanites; Christians, Sunnis, Alawites, Jews, and Shiites. Many came for her company, while others came for her help. Sect or ethnicity was never the key to entrée. Rather, she welcomed folks whose conversation was entertaining, whose power could be leveraged, or whose talents included the ability to see the future in an overturned cup of Arabic coffee.

But particularly, she opened her door to those who knocked on it in need, often providing an alternative to the ruined systems—political, legal, economical, or societal—that failed them, especially those who were outsiders, because of their gender, their class, or because they were not Damascenes.

Some needed assistance navigating the government bureaucracy, which she helped them bypass by giving them the name of the right bureaucrat to bribe.

Some asked to borrow money as they stood at her door. After giving them tea inside her house and hearing their plea, she would retrieve the needed amount from her armoire. Sometimes she just provided shelter, on mattresses dragged to the living room floor in makeshift accommodations, to those who came from the villages near Hama and who had business in the capital, like the woman who would visit her son monthly in the insane asylum in Damascus.

Others’ needs were more urgent; she once convinced a general she knew socially to imprison a young conscript who had impregnated the girl he loved, but whose parents refused to allow him to marry. The would-be love was—like the Assads—an Alawite. Like many of her sect, she was of little means and worked as a domestic servant. He was the son of bourgeois Sunnis, who, like many of the bourgeoisie, believed the Alawites to be of the lowest and untouchable rung of Syrian society. My grandmother would not have it. For the young man’s parents, the sight of their son in prison soon caused them to relent.

She always cut quite a figure, tall in her heels from Beirut, a Kent cigarette never far from her lips—from which witty and acerbic commentary was always forthcoming. But though those deep inhales gave her voice its sexy huskiness, they would ultimately render her mute in 1980, perhaps the worst of the paralysis caused by the stroke brought on by all those years of smoking. A vibrant force, she was suddenly crippled, broken, and hovering in a suspension—but not termination—of life. It is called Locked-in Syndrome. She could no longer move, no longer talk, and only blink her responses and thoughts. Yet, all those whom she had hosted came to visit her regularly.

A year later, in a message to all Syrians, Hafez al-Assad broke Hama, where resistance to his power had been growing in the form of the Muslim Brotherhood, an albeit malformed, grossly imperfect creature, but of course a product of what gave rise to it—much like her responses to the systems that constricted her life and the lives of the others.

He murdered, by conservative estimates, ten thousand people, forcing the entire city of Hama to collectively pay the price for giving rise to people with the temerity to engage in politics. He also killed off much of the will of any Syrian to participate politically—making it clear that the cost for exercising such a right would be borne not just by individuals, but by their family, their neighborhood, and their city. It was a higher price than most people could commit others to pay.

The official memory of Hama was to forget. Syrians never knew exactly how many were killed, and family members still do not know who is dead, when they died, or who is in prison. Of course the official amnesia precluded any kind of national mourning, and the country remains suspended in the lack of truth, accountability, and reconciliation.

As for my grandmother, for years she languished in a room in her limbo while everyone waited for an end or a beginning; for life to begin moving again.

Then in 1987, after seven years in still and silent stagnation, she left them and this world. She was buried in the cemetery facing the site of the hole in the still-standing wall from which Paul escaped in a basket.

In choosing what to keep of her, we too chose our official memory; even though it had been years since she could sit, stand, or let alone walk, we kept her shoes.

***

Of those that made up my grandmother’s circle of conversation and sisterhood, I was particularly fond of two women—sisters who doted on me as a child. One of them joined my grandmother daily at lunch, whose flat was nearer to the beauty parlor where she worked than her family’s house. Occasionally in the years of her illness, when the sisters would visit my grandmother, they would telephone me across the world where I was then living and hold the receiver to her ear so she could hear me, but not talk back to me.

As I became aware of religion—which in the 1970s in Syria seemed only relevant for who could eat what when, who got presents on which holiday, and who could marry whom—I learned that these sisters were Jews.

When I returned, in 1992, after several years away and years after my grandmother had passed, I asked for them. Only then did I learn that they were gone. Just months before my return, Hafez al-Assad had lifted the ban on Syrian Jewish families traveling together, and the inconvenience of the complexity of being Syrian and Jewish—for both Syria and Israel—was shamefully resolved. The resulting mass exodus meant the Jewish Quarter, thousands of years old,and nestled along the still-named Street Called Straight where all those years ago Saul had awaited sight, had suddenly gone dark.

Thus, after nearly twenty years of removing opponents, dissidents, intellectuals, and others who could or would not belong through disappearances, murder, imprisonment, and encouraged exile or emigration, and ten years after removing the Islamists in Hama, the regime amputated yet another limb.

With their departure, Syria began to take leave of the conception of a Syrian identity that rose above our parts to a sum made stronger for its diversity. Further giving in to the utter lack of imagination that would prefer homogeneity—mistaking it for simplicity, silver-tongued and soothing.

***

Eight years later, Hafez al-Assad finally died, and we hoped our suspended time and suspended lives were over. But the opportunity for a good Syrian rupture was missed, and passed over as power was passed on to his son. For eleven years, Bashar al-Assad, the supposedly mild-mannered ophthalmologist, and his pretty wife put a young, fresh face on dictatorship.

Across the street from the National Museum arose a glamorous Four Seasons Hotel; new cars were finally legal; foreign tourists poured into the bars and boutique hotels on the Street Called Straight; and one could at last get a Coca Cola instead of having to settle for the domestically produced Master Cola— the only similarity between the two being the red and white packaging and stolen font. Additionally, a few people, particularly those related to Bashar or from his Alawite sect, got quite rich. But in some ways, it did feel like Syria had started moving again.

With these supposed markers of progress, plenty of people inside and outside of Syria were willing to overlook the presence of an authoritarian regime in Damascus. Brad Pitt and Angelina Jolie visited the country, chilling with Bashar and his wife. Not only was it acceptable to be a dictator, it was also A-List cool. Those gloomy and suspended days of his father seemed so far in the past.

It appeared that kinder, gentler dictatorship would be the way forward for Syria, with Syrians playing no role in determining their political fate, something many seemed willing to accept. For those who would imagine a democratic and free Syria, such complacency and complicity among their countrywomen appeared as much of an insurmountable barrier to a new future as the countless secret police and security apparatuses that spent much more time keeping Syrians afraid and in line than defending the country against any external threats.

Then, a spark of hope was lit on 25 January 2011, when Egyptians broke through the fear that had held them back and helped keep their dictator in power all those years. That it was happening in Egypt—in many ways the elder statesman of the Arab world—suggested that what had happened in Tunisia (more of a distant relative) was not just a fluke. 25 January was a declaration, reaffirmed again this year, that Egyptians (cheered on by the Arab world) were embarking on a new path for the future, which by definition had no room for the rulers or ways of the past.

Coincidentally, though perhaps cosmically, 25 January is the day Paul’s conversion on the road to Damascus is celebrated.

***

In the wake of the Arab awakenings and the exile of Ben Ali, the trial of Mubarak, the lynching of Khadafi, and the abdication of Saleh, all eyes are on the next teetering domino.

But it remains an unresolved vigil, even as those newly initiated democrats in other Arab countries move on – debating, invalidating, and revalidating God, constitutions, and polls.

Syria is anew with defections and conversions to a movement that would again shake the nation, splitting once more not only the ranks of today’s soldiers, but also those of relatives, neighbors, colleagues, and friends.

Geopolitical winds—breezes and sandstorms—continue to blow through the country, and in their frenzied shifting, different empires again vie for her. The vices of each contender, however, have left many a Syrian wary of the future. And so, many ruptures and breaks, personal and political, have given a new generation of Syrians a taste of blood and bitterness, while seeing to it that older ones never forget.

In the spring of 2011, just as the protests began, and just before Syrian Christians prepared for their Easter celebration of resurrection and rebirth, I began the final stages of renovating my grandmother’s first house, the one she moved to as a bride when she came from Hama, when modern Syria was brand new. We had finally succeeded in evicting an Army soldier who had been squatting for nearly forty years, even though he had moved in as a tenant after my grandmother had moved her growing family to another house. Recently, a change to the property law, which for so long had protected such rent-free tenants, gave owners the right to evict such people if the owners paid the squatters to leave—to the tune of forty percent of the house’s value.

Is the regime seeking a similar deal?

The soldier had sullied the beautiful mosaic floors and had done nothing to update its paint, its plumbing, or its wiring. But it was otherwise intact and recognizable, enough so that my mother and aunt could guide me through its memories—here they would secretly watch the TV, past their bedtime; there was the spot where the unruly children upstairs dumped water from their balcony to ours, drenching my great grandfather’s head; and this is where, once a month, on a mattress in the middle of the living room, the lady with a son who had gone mad would cry herself to sleep.

Even as chaos swelled that fall, stranding workers in their towns outside central Damascus, the modest renovation continued. By the end of 2011, all the house’s internal workings had been overhauled and the floors restored where possible and where not, replaced with something new.

I moved in alone, kept company by the house, my grandmother, and those other ghosts gone by.

But as a long winter approaches Syria, I wonder what fragilities will be felt and seen—if it can remain a home, both intact and welcoming. Already in the cold and short days of last December, January, February, and March, shortages of diesel and electricity kept us shivering and in the dark, the house’s old wooden windowpanes and shutters shrunken and unable to keep out the bluster.

At night, after I have turned out the lights in the house and I listen to the sounds of disintegration, I wonder: will we wake to find ourselves disappeared?

We know we are irrelevant for a ruler who would reign as long as he lives, or for empires who would conquer by proxy.

Flesh or stone or limb or wood or country—casualties have been easy to make, and we would all be claimed.

Nevertheless, it is a lovely house, surrounded by grapevines and citrus trees of every kind. Light fills it and breezes drift through it, and even though it cannot hide that it is old and once abused, it is clear that it has been re-taken by those who loved it and would love it again.

![[Bab Kisan, now the Greek Catholic Chapel of St. Paul, where by legend disciples lowered Saint Paul in a basket, helping him escape from Damascus. Image from Wikimedia Commons.]](https://kms.jadaliyya.com/Images/357x383xo/1024px-Damascus-Bab_Kisan.jpg)